[Review originally published on Bookmunch: View Post]

How many female writer-walkers can you name? We think of Dorothy Wordsworth (though we also instantly think of her brother); we think of Nan Shepherd (mostly thanks to her sudden popularity over the last few years); perhaps we think of Cheryl Strayed or Raynor Winn. But how can these women compare to the fame of the Lake Poets, the flâneurs, D. H. Lawrence, John Muir or Henry David Thoreau?

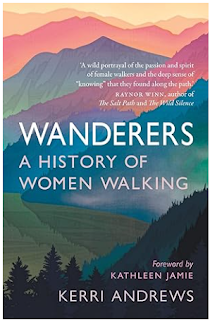

Wanderers: A History of Women Walking by Kerri Andrews (introduced by Kathleen Jamie) makes a strong case for remembering that there is a reason behind the history of walking coming to us from an overwhelmingly male perspective.

In this collection Andrews rounds up some of the most well-known (and some less well-known) writer-wanderer women who, for one reason or another, were passionate walkers throughout their lives. So much more than an anthology, each chapter is dedicated to a single woman and a meditation on the role that walking played in their lives. Through their walking habits (and what these habits inspired), Andrews paints vivid characters rather than presenting biographies, yet gives plenty of insight, and shows intimate knowledge of the backgrounds and output of her chosen examples.

The curated selection is colourful and exciting, and their reasons for walking varied. There are those we expect to be included, and those we get to know, perhaps for the first time. Elizabeth Carter, the whimsical vagrant, walked each day for inspiration and health, ideally also enjoying a good drench in a thunderstorm; Dorothy Wordsworth used walking as a way of ‘experiencing both her new-found independence and her new home’ after moving into Dove Cottage. Harriet Martineau, after a prolonged illness that confined her to a single room, rediscovers the joy of living in the act of walking, roaming the Lakes for ten glorious years and rivalling the Lake Poets as a writer-walker in her time. Virginia Woolf paces her novels into existence, while Anaïs Nin – diarist and writer – explores her sexual desires and creativity on the streets of Paris and New York.

What becomes clear from these essays is that walking can be a lifeline or a source of creativity; it can be a form of memory, and can transform a city or landscape into a vast spider web of lives lived in parallel.

Andrews also explores the limitations on women’s walking – not everyone is permitted, or is able to walk, and not freely in any case. Most women in this collection have some reason to fear, whether that’s judgement, assault, or household and family duties that husbands historically extricated themselves from. These women didn’t have the liberty to walk where and when they might have wanted and, arguably, women today often still don’t. With these essays, Andrews raises a rallying cry against giving up on a pastime that, as Rebecca Solnit writes, is a ‘portion of our humanity’.

Each chapter is bookended by a short piece by Andrews – some recounting personal experiences of walking, and some offering reflections on these extraordinary women. It’s a perfect balance, and the structure works very well in tying all the chapters together.

It’s not so much a history of walking as a historical tracing of a line, a trend often overlooked. It is a much-needed case to be made, and Wanderers sits proudly unique amongst the many walking anthologies that give a mostly male perspective.

Overall, Wanderers is more than history, more than anthology: with an excellent selection of case studies, it is a love letter to walking, and highlights time and again how this simple act can be true freedom.